|

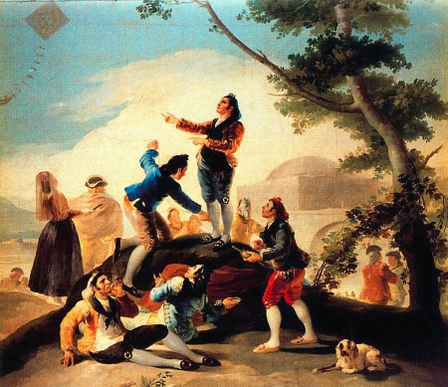

It’s maybe 30 degrees, but to my Scottish skin it feels like 45. There is no shade. I remember seeing a photo of Igor’s in March where people were sheltering from the driving rain here under tarpaulin. We are in a long queue to cross the border back into Poland. We get the giggles about something and I look up and catch eyes with a woman who looks back at me with the saddest question in her eyes, ‘how can you be laughing?’ I glance around the queue. While people are chatting quietly and children entertain themselves, poking sticks through the railings, no-one is laughing. No-one is smiling. I wonder how it would be if Cuckoo and Maybee arrived here. If these people had permission to laugh, would they? I recently heard an interview with Volodymyr Zelensky where he said, 'Humour is part of ones being...it is important, as it helps one not to lose their mind'. Our fits of giggles are just that - a release that brings us back to ourselves. I hope laughter is not lost for long here. Soldiers are crossing back into Ukraine in an endless stream, heavy bags piled on their backs as they trudge up the hill, each step bringing them closer to the front line. I think, ‘that could be Igor. That could be my brother’. But it isn’t. The people queueing don't acknowledge them in any way, and the soldiers gaze is fixed straight ahead, until one soldier shouts, 'Slava Ukaraini!' and everyone in the queue responds, 'Slava Ukraini' in one voice and then they return to their own worlds. 5 hours later we reach the turn-style and a Roma family bundle through in front of us - grandma, mother, children, babe in arms. There seems to be an issue with documentation, and I begin to accept that the train back to Rsezow probably won't happen and that maybe I’ll miss my flight home. This seems a certainty when a group of Polish men push their way forward next. Huge, shaved heads, each with a bottle of vodka in their hands, shirtless. The change in energy is dramatic. I realise that for the first time since I've been in Ukraine, in this war zone, I feel unsafe. This particular brand of masculinity, entitlement, aggression is so intimidating. I feel small and snappable. The security guard asks to check my bag, and as I open it, a pink tulle underskirt bursts out to greet him. Still no smiles, but it does somewhat mitigate my silent humiliation at him rummaging through my dirty laundry. Passports checked we run back across the border, back down the tarmac path, past the Unicef tent, grab a banana, water and a bowl of cooked potatoes from the wonderful World Food Kitchen and race to the train with minutes to spare. So sweaty. So tired. So hungry. We arrive and there is no sign of the train, no rumbling of tracks. We check the timetable. We check again. I look at my watch, I look at my phone. I look at my watch…we are in a different time zone, we have an extra hour. Our journey back to Warsaw becomes a kind of endless repetition of this lurch between despair and hope, involving a cancelled bus, a missed train, a rogue taxi, train fines, information desks with no information, a hotel that we can’t get into and which when we do, well after midnight, has no running water. But I do get home, safe and sound. Once I am there I know something has shifted in me, but I can't articulate what it is or what it means. And then I went to Madrid and saw Fransisco de Goya paintings in real life and something clicked. I saw his early ‘cartoons’ of ordinary Madrileños in the countryside, relaxed, off-guard, playing, drinking, eating. Blue skies and open, innocent faces: Then I saw the enormous ‘Los Fusilamientos del 2 de Mayo de 1808’. A scene depicting the death by firing squad of civilians who had attempted to defend Madrid from the French in the war for independence: Then I went to the ‘Black Room’. A series of paintings that Goya did towards the end of his life, having witnessed the atrocities of war. He painted them across the walls of his house. Despair, grief, fear, desperation fills the space, pours off the canvas. The atmosphere is thick with it. It prickled my pores, filled my lungs, squeezed my heart. My body sat down and tears streamed down my face. I realise that the tears are ones of acceptance. These paintings of gaping black mouths twisted in anguish bring an incongruous sense of comfort. He has created an invitation to acknowledge the things that we are otherwise encouraged not to see, or encouraged to minimise, or brush over. They show us the darkness of our shadows, the acuteness of our pain, the inherent violence of life, the violence that resides within all of us. They show us suffering that shouldn’t be shown and in their unremitting honesty remove all sense of shame from that suffering. They are a mirror that is as honest as it is compassionate. Sitting here in front of these images of pain and anguish, letting all of that in, I feel comfort and hope. These works of art are a courageous act of love.

At the end of the room, there is one painting that doesn’t quite fit. It has an orangey hue, and two thirds down the canvas, there is the muzzle of a grey dog lifting itself up over a brown wave. The dog is clearly drowning, but its face is looking up towards towards a person, maybe, that we can’t see. To me, the look on the dog's face is one of hope. And this is it, isn’t it? Hope wont stop us from drowning, wont end the war, wont stop children getting sick and dying, wont cure cancer or Alzheimers, but it can make this moment more bearable... And I suppose that is why I am a therapeutic clown.

3 Comments

Woken twice by air raid sirens last night but didn’t consider going to the shelter - immediate need for sleep trumps abstract sense of threat, I guess. Thinking about yesterday’s workshop and how it went, and this afternoon’s visit to the IDP centre with the UA clown team…They asked for input on working non-verbally, working with groups and the therapeutic side of their practice. This was our focus yesterday, and it is what we will continue to focus on today…and so it’s time to see how much, if any, of that has landed. I'm feeling a bit nervous about clowning with them - a familiar little voice 'helpfully' reminding me of all the ways it could go wrong. The role of playing a ‘maestro’ who is all-knowing and untouchable is a seductive one...but it does have its flaws… She sits there with her glowing white clown halo, and her enormous clown wings, hovering on her plush, red velvet clown throne. Her clown disciples sit at her big old clown feet as she regales them with anecdotes of clown glory past. Her secret knowledge about what makes a good clown forms a radiant shield around her. Everything she says is met with either wonderment, laughter, or frantic note-writing. She is an all powerful clown guru. Her disciples ask for a demonstration of her gift. She duly stands up…and her pants fall down. And everyone laughs. And she tries to pull them back up again, and falls on her face and they laugh even more. And as she stands up to try to explain that this isn’t part of the lesson, they think this is part of the lesson and nod in wonderment again and take more notes. And the harder she tries to deny it the more notes they write until her frustration builds and turns to tears, and they are so moved by her performance that they start to cry too. And as the sobbing gently subsides, somebody exclaims with inspiration ‘thank you guru, I have finally learned that the secret to healthcare clowning is to pull my pants down’ and everyone agrees and a week later they are all arrested for assault and indecent exposure. As healthcare clown teachers we have a responsibility to demystify this art form and open its doors with just the right combination of clarity, playfulness, absurdity and precision, because the people we are clowning for are not paying customers, they are people experiencing extreme adversity in some of the most horrible circumstances imaginable. Putting ourselves on a pedestal as ‘maestros’ doesn’t make sense when the real secret to doing this job well is continual professional development, individual enquiry, and practice. When ‘success’ is making a teacher and peers laugh in a controlled workshop setting, what are we learning about how and what to apply at a hospital bedside? It is not only important to us to ensure that the Ukrainian clown team is able to integrate what we explored in the workshop yesterday and apply that to real life scenarios, but that we also embody what we teach. By meeting the team as equals, we are able to demystify what we are teaching and make it concrete and applicable. We show that we are also learning, falling, trying again - that we are also vulnerable and fallible. Good artistic practice requires us to be clear about our intentions so that we can hold ourselves to account and assess progress on our own terms (our ‘trying again’ is informed by a reflective practice). This not only applies to our work everyday on the floor as clowns, but also our teaching. There is nothing for it. We have to put our money where our mouth is, lay our noses on the line, put ourselves in the shit and clown with the team at the IDP centre together…just as soon as I’ve eaten a sensible lunch… Today was my first time working at an IDP centre. Luckily I am too tired for imposter syndrome. Reflecting on the importance of starting well and a way to clown with groups when chaos is on the horizon: I felt rushed by the knocks and calls for clowns from the children outside. It felt like the energy from outside was penetrating the walls and drawing me towards it. My mind slipped outside, and started assessing, problem solving, trying to play the games before they were played. These thoughts happen so fast they are barely conscious. My heart beats faster, breath becomes short and rises to my chest and shoulders. These are all familiar red flags telling me I am not here. And I know that if I am not here, I cannot clown. The surest way to be in the here and now, to be present, is to bring our attention to the body. While thoughts can time travel, and spirits soar across the cosmos, our bodies always stay put. The more impatient or anxious I am to get started, the more important it is to bring my focus to my breath and ground myself before I put on my red nose. It is like grounding an electrical circuit - excess energy is safely released, energetic flow is restored, and I have more space and time to respond to whatever it is I am about to encounter. I know from experience that this is an emotional safety measure I cannot skip before going on the floor. The anxiety and excitement amongst the UA crew was tangible, so I led a short breathing and grounding exercise. It is always an interesting thing to do - to invite someone to stop and land when they are already out of the door in their minds. This first out-breath was delicious. The energy shifted. We created space and time with a simple inhale and exhale. Another step that cannot be skipped is our physical warm up. Igor led this beautifully, with lightness and humour, as we connected to our bodies, our clown spark, our stupidity and sense of wonder. And once we were ready, our task was to open the door, step out, and be the most boring clowns this universe had ever seen. Stepping out into the courtyard was like stepping into the sea. However slowly and calmly you go, the more you move, the more turbulence you create. The more people that enter the sea, the harder it is to control the turbulence. Children’s hands start going into your pockets, your nose becomes a target, your boundaries are breached and water starts rising. Your clown dives overboard and swims for dear life, and your pilot has to take control of the rudder, in full survival mode: When you don’t create a clear game as a healthcare clown, you become the game. Igor and I sensed these rising waves and instinctively felt the need to be still, create space and let the waters settle.We stood for a few minutes. Maybe this looked like ‘doing nothing’ but in fact, our stillness was embodied and intentional and grounded. We were listening and waiting. This provoked curiosity and we were joined by others who were attracted to this stillness. Soon enough, the waters settled and a circle emerged, a calm pool at its centre. We were a mixture of children and clowns, all looking towards Cuckoo, who was ready. He made a movement and paused, and we copied. The children understood immediately and copied too. We saw straight away the ones who were more confident, more reticent, more active, less able to focus, more eager to please. As clowns, we can adjust our movements, tempo and rhythm to meet what we see. For a child who is full of energy, this might mean using big slow motion gestures that they mirror - tensing their muscles and using up excess energy on a big movement. For a child who is reticent, this might be noticing what small thing they are doing, and offering it back to them as a gift. Before long, we were all in a shared moment of carrying, or trying to carry, giant rocks. Everyone fully committed to helping various clowns who had got themselves into varying degrees of difficulty. We were maybe fifteen people, playing together. The game is clear, our boundaries are clear, we are safely on dry land and we haven’t spoken a word. A wonderful thing happened in our second session. Without Igor or myself initiating it, the UA clowns found themselves in full flow of a game that seemed to have a life of its own. When I joined (I can’t remember now what absurdity Maybee was absorbed in before this…), the game seemed to be that two guards held down cardboard tubes like a gate, and we had to find ways to pass through. Children and clowns were collaborating all over the courtyard to find ways to pass. I noticed one duo that was intently focussed on delivering a long stick over the line. It appeared extremely important that this stick was to be held between the very tips of two people’s fingers.

Sometimes a bold invitation is required to bring someone into a game - to shift their focus from the inner world of self doubt to an outer one of collaboration and connection. Maybee noticed a boy who was watching from afar but uncertain about joining in. She commandeered his bicycle…hands on handlebars, bum settled on the tiny saddle, foot on pedal, tongue out…and realised she had no idea how to set off. She held out her hand and the boy took it, instinctively. Only once their hands were locked did a flash of doubt cross his face. Maybee replied with a look that said, ‘but you are my only hope!’. He rose to the moment, said yes and balanced her sweetly and carefully all the way across the courtyard as she wobbled and weaved. Brief eye-contact with the guards, and phew! The gates lifted! They were allowed through! Overwhelmed with joy, cheering as if she had just scored a winning goal in the world cup final, she cycled triumphantly back around to the front, the boy trotting alongside, laughing. He immediately got back onto his bike and pedalled towards the gates at super-speed, keen to check if it would happen again, keen to repeat this exhilarating hit of liberation and acceptance. Huge cheer and applause. Now that he was sure it worked, it was time to share the joy. He mounted his tiny baby brother onto the saddle and carefully pushed him across the barrier - sure enough - more cheers. They did this again and again and again, and were soon joined by more bikes and scooters and roller skaters. The instinct of a child is to heal themselves through play. The question for us is how we support this instinct as clowns. The answer lies in the very foundations of our practice. We all have it, and all we need is to embody this principle to our very core – to say Yes. We practised this yesterday afternoon in the workshop, and I was so moved and thrilled to see it playing out here, and working so beautifully. By repeating the word Yes over and over again, regardless of how excited you feel, it gradually becomes internalised – it transforms from an abstract word to a way of being. The yes becomes embodied and automatic. The guiding principle is that my partner's ideas are always wonderful and I am always excited to celebrate them and help them to grow. When this principle is reciprocated, the game gains momentum and energy of its own. When you know that your partner is going to love every offer that you make, regardless of its quality, there is no need to worry about being ‘good’. You don’t need to know the correct response to an offer or your environment, only that you will accept it and love it. This is how children play, of course - we adults have to re-remember what we once knew instinctively when we were young. Uncertainty increases our stress levels and an automatic response to that stress is to attempt to reduce uncertainty by rejecting the reality of other people, to say no to the environment, say no to any offer that isn’t your own, say no to anything that doesn’t have a clear outcome, in an attempt to regain the feeling of being in control. Our goal yesterday was to make sure that by the end of the day, the clowns were sure that the only thing they needed to know was that they would say Yes to everything; Yes to their first idea, Yes to the child's intuition, Yes to their spontaneous offer, Yes to the role they choose, Yes to every single suggestion they make. In this way we play, we create, we grow and flow without any space for doubt. And the simple Yes is enough - there is no need for the clown to understand what it means or to judge. …so it is only now that I am changed and resting that it has dawned on me that we were playing a check-point. ‘Guards’ decide at what moment to lift the barrier - whether to say yes or no. ‘Citizens’ are free to invent new ways of crossing, experimenting. Here it isn’t documents they have to present, but flair, ingenuity and comradeship. And they are all allowed through. Therapeutic clowning, non-verbal play, working with groups: check. Putting ourselves in the shit: double check. |

AuthorI am a therapeutic clown and performer. Writing here is part of my wider practice and maybe some of my thoughts will trigger some thoughts of your own and I hope that helps. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed