|

It has been a strange thing, over the years, making the transition from student to teacher, especially when I feel I have so much still to learn. Part of me had a hang-up, from school I guess, that if you are a teacher you have to know everything. Finding a balance between being authentic about my limitations, while also honouring what I have learned over the years has been challenging. Seeing a group of participants become less and less comfortable as I start a session by saying, ‘I don’t know anything, I’m probably explaining it wrong…’ was a lesson in the importance of knowing what I know. I have learned some valuable things, and I am able to communicate those things clearly and with authenticity.

Over the years I’ve been taught by many wonderful clowns and teachers - all of them have enriched my practice one way or another. But it took me years - until I worked with Ira Seidenstein - to realise that the trick isn’t to want to please your teacher, but to want to please yourself. If my intention is to learn how to make more people laugh more often, then I can measure this and practice this in a workshop setting for myself. If I’m not making people laugh, but they are engaged and interested, maybe I can learn something else about my practice that might be of value, or maybe I just need to change what I’m doing. If my only intention is to please my teacher, to fit into their particular school or style of clowning, then when I leave the workshop I will have very little to go on other than to mimic their style and school. As an artist or clown, you can investigate, go and see and test in any way that you want, in any context that suits you. Your practice means that you are responsible for setting your own intentions and goals, and for holding yourself to account. You can monitor your own progress on your own terms, analyse your practice, find weaknesses that you want to build on and follow your own interests. Your aim isn’t to become your mentor, but to become an artist who can express themselves fully and freely. The reality is that studying with any one ‘maestro’ doesn’t make anyone a good clown. Studying with Gualier requires time and money but zero skill, aptitude, talent for clowning. You pay, you go. It’s not to say that his teaching isn’t highly respected, admired and that he hasn’t witnessed the birth of many a wonderful clown. But paying for workshops isn’t the only way to learn and grow and progress as a clown - the point of arrival isn’t at the end of a 2 week clown intensive. I have realised that as a teacher and coach, firstly, I can only be myself. I know that practice is important to me, and that I am constantly learning. My aim is to provoke you to think and reflect for yourself. I can give you feedback on how well you are achieving your intention, but I won’t tell you if the content of what you are doing is good or bad. I’m not, and never will be, qualified to do that. As a healthcare clown, you have to be able to analyse what you are doing and what you have just done. You have to be compassionate and non-judgemental about that in order to be objective about what is connecting and what isn’t so that you can continue to serve the people you meet to the highest possible standards. That applies to my teaching practice too. All of us are part of a lifelong learning process, constantly evolving and growing and ultimately responsible for ourselves.

1 Comment

I’m grateful that Igor has taken on the role of chief navigator for our trip. He has perhaps noticed my tendency to look carefully at the google maps route and then, unwittingly, but with gusto and confidence, walk off in the opposite direction. It means that I have barely noticed where we are going this morning, as we zig-zag towards our workshop space, I don't even know the name of the building or the address. I am relaxed, gazing up at the blue sky, skipping along every so often to meet Igor’s giant stride. We meet Evgeniia Arakielian, who had organised this workshop for displaced children and their parents, and head into the basement of an office block. The walls are colourful, the floor scattered with bright bean bags. The room doubles as a bomb shelter and (for the next few hours) our workshop space. When I imagined shelters before coming here, they weren’t like this. I imagined lots of fortified concrete. This is basically my old office. I am at ease.

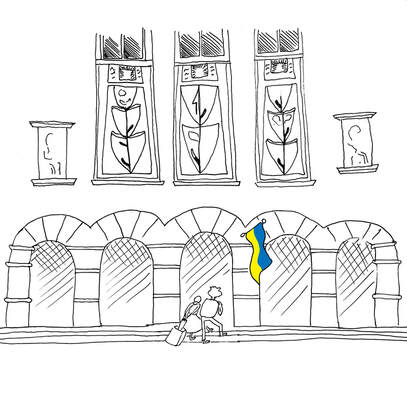

We start to limber up, check-in with one another about the space, our plan. Evgeniia goes up the entrance to welcome participants. Her phone starts to flash and says something on speaker mode. The something is in Ukrainian and repetitive and urgent sounding. Evgeniia comes back down the stairs and says, ‘Siren’. Her tone is one of resignation rather than alarm. She looks at her phone - an app tells her where and how severe the risk is. We seem to be in an area of the map that is currently flashing RED. Red is never good when it comes to warning systems. I say, ‘Belarus?’ she looks at me and shrugs, ‘yes?’. The space beneath my ribs is suddenly ice cold and hollow. My fingertips tingle. A hideous rapid fire slide-show flashes through my mind, each image more catastrophic than the last. Darn my vivid imagination! I can feel the pulse in my neck, my mouth is dry. I look at Evgeniia - she seems nonplussed, if a little annoyed that it means people might not come to the session. Okay. At least we are in a bomb shelter, I guess. I follow her lead - I breathe and get on with it. After some confusion, where I tried to recruit some, in retrospect, very adult looking Red Cross aid workers into our workshop for children (Don’t make assumptions about people’s age! Do ask people why they are there!), some actual children and their parents arrived, despite the siren. We knew from Evgeniia that our participants were principally experiencing a loss of sense of self and identity since being displaced from their homes. That a lot of them were sad that they had to leave pets behind. We had tailored a workshop to fit these themes, that left enough space to incorporate whatever arose in the moment. The young people were a mix of energies and ages, from a young boy who didn’t stop moving for the whole session, to a teenage girl who was so introverted, shoulders hunched, head down, hands clasped in front of her body that she barely moved at all. I was touched seeing the parents standing in the circle with us and imagined that they might be feeling as nervous as their children as we introduced the session. When was the last time they had played like this? We were on a quest to find a magical portal that would give us whatever treasure we most needed to help us feel free and strong and happy. There were many challenges on the way - a magic mirror, a desert filled with cats, a huge abyss, a Tiger Forest..all animated and embodied by the group. We found playful and imaginative solutions to each problem together, making sure each idea was heard and incorporated - How to pass through the magic mirror? Find your twin and go together! How to cross the desert? Become a giant elephant! Each person plays a different body part! How to cross the abyss? Blow up imaginary giant balloons and float! How to cross the Tiger Forest? Learn how to hunt tigers! I am interested to see how the young, introverted girl is handling this so I keep my eye on her. There are plenty of places and opportunities for her to sit out if she needs to, but she doesn’t. She stays alongside the whole time, watching, hands clasped. During the Tiger Hunt, I see her flinch at the sound of us making a drum roll on our knees. Then when a toy car accidentally hits Igor’s foot and he leaps off the ground like a cat, she giggles and looks at me and we both giggle together. Her shoulders drop about 3 inches. The next time we drum roll, she joins in, smiling. When we reach the portal, made by our own hands, and we are finally ready to reach in and take what we need, what we’ve found on our journey together, I am trepidatious. This is a bold invitation and I worry for a moment that the game won't be accepted, that the portal will be left impotent and unused. But a moment later, a dad reaches in, ‘I take out love for my son’ he says as his son gazes up at him. Now his son reaches in, ‘a cat!’, someone else, ‘a sense of security’, ‘Friendship’, ‘cat food!’ the boy dips in again. There is a pause. The young girl who could barely move looks at me - she knows it is her turn, but she seems afraid. ‘Put your hand in’ Igor says simply, and she does, ‘a cat!’ she says, smiling, the first and only words she utters all morning. And so the portal has delivered love and security and friendship and cats and food enough to feed them. It’s only when I get home to the UK that I read how many pets have been left in shelters and that these shelters have very scarce and dwindling food supplies. My heart breaks a little that these children might be aware of this. A mum says at the end with tears of joy in her eyes, ‘I haven’t felt this way in years!...it was just the best, the best, the best…!’ and I find myself awestruck by this woman speaking of happiness and joy while we are all standing in a bomb shelter surrounded by children during a Red Alert siren. It’s a timely reminder; ‘Of all animal species, humans are the biggest players of all. We are built to play and built through play. When we play, we are engaged in the purest expression of our humanity, the truest expression of our individuality. Is it any wonder that often the times we feel most alive, those that make up our best memories, are moments of play?...But when play is denied over the long term, our mood darkens. We lose our sense of optimism and we become anhedonic, or incapable of feeling sustained pleasure” Stuart Brown, Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul We give each participant a red nose to take with them - a reminder of what they found here together, and that they can keep it with them, always. The shy girl put hers on, briefly makes eye contact and smiles. Soon the shelter is empty again, echoing with images of a father playing at hunting tigers with his son, a mother being the trunk of an elephant, a teenage girl trying to convince a mirror that she is twins with an adult woman. Echoing with the sound of jungle birds, desert cats, tiger roars and laughter. We step out onto the street, into the sunshine and I notice how the workshop worked on me too - from the moment we started until this moment, I had forgotten about the war, the siren, the RED threat, and I felt like myself again. A very hungry version of myself. It was time to find Pizza before our afternoon in the IDP centre. Text by Igor Narovski & Suzie Ferguson Towering before us, like a cliff, like La Scala opera house, stood The Lviv Academic Puppet Theatre. Above five gigantic arches hung three vast coats of arms that would befit a mediaeval castle. Their designs shifted seamlessly between theatre mask, war shield and back again. In this building's shadow, we ourselves became puppet-like - small and fragile, revived for a moment by the will of the puppeteer, by the will of their hand. In front of the theatre, a long bench stretched across a wide square. On it, we laid our sweat-wet costumes to dry after our hot shift at Lviv Regional Children's hospital. Suddenly, as if from the Gods, a woman dropped into view. “Igor? Suzie?” “Yes,” our puppet heads nodded. “Marichka,” the woman introduced herself. “I’ll show you the room for your masterclass. Just give me a minute, I'm dying for coffee…” While Marichka grabbed her coffee, we rolled up our laundry, packed our dry, sun-smelling clothes, and got ready to follow our guide into the puppet kingdom. And off we went. With each step, the Puppet Theatre advanced as its monumental facade reached skywards. Colossal archways hovered overhead. To the right of the entrance was a poster - not an advert for a performance but a sign leading to a bomb shelter. As the magnificent door to the Puppet Kingdom loomed before us, its wooden handle met Marichka’s hand. She gently pulled it. As if under its own weight, by itself, just waiting for the slight impulse of a human hand, it swung open. The dark, cool hall appeared before us, revealing a solemn marble staircase that led to the finest heights of puppetry. We stepped over the threshold and entered…not the Puppet Theatre, not the salve of its cooling marble, but into the bright, white, studio in Glasgow. We’ve entered the past - two weeks ago, when we were preparing a master class program for Ukrainian clowns… It dawns on us that in going to a war zone to work with clowns who are living through war, who are working with children displaced by that war, we cannot, not address the war. And as this realisation settles in the gut as truth, the question, but how? bursts through the solar plexus. It is starkly obvious that we are not in the same place as these clowns so how do we talk directly about war, coming from our privilege? How do we balance keeping the space emotionally safe while honouring these professionals with the artistic rigour & respect they deserve? How deep do we ask them to go? How much should we provoke? Why is it worth the risk of travelling across a war zone to attend? What if someone is shelled on their way to get to us? We realise that this workshop is an act of mutual aid - professional healthcare clowns with time and resources helping out professional healthcare clowns who are in need. Their need is unique: They are experiencing the same war as the children they visit, the same horror, devastation and fear. How can they be playful, creative and present with this as a backdrop? It occurs to us that we don’t need to invent anything new - we can apply our healthcare clowning practice to this context. Working in hospitals, we know that if our tendency is to run from our own emotions, we will run from other people’s emotions too. Our resulting work will be superficial - we will dodge and distract rather than validate. There is a difference between when someone tries to distract you or fix your situation; ‘It’s raining and i'm cold and wet’ - it’s fine, you’re going to be okay, it’ll stop soon… And when they acknowledge your situation and empower you to feel your own agency; ‘It’s raining and i'm cold and wet’ - yes it’s raining, I see that you are cold. What would you like to do about it? If you avoid your own emotions and needs as a healthcare clown you will find yourself standing in the rain unable to use your umbrella because you haven’t acknowledged that you need it. Accepting the fact that it’s raining and that you are cold and wet means that you can put up the umbrella that you have been holding in your hand the whole time. Only at this point can you invite someone to shelter with you, or help them to put up their own umbrella. Our goal was to help the Ukrainian clowns accept ‘the rain’ and find their ‘umbrellas’. An idea emerges to create a map that guides the group back to 24th February, through their own experience, making sure that they are in a safe enough emotional territory to slow down, feel again and reconnect with themselves. Once re-tethered to this inner-wisdom, we can journey onwards to their work as Healthcare clowns and make the shift from victim, ‘it happened to me’ to clown ‘okay it happened, i've learned from my experience and I’m ready to play with it’’. The shift from ‘I’ve found and opened my umbrella’ to ‘I become someone else’s umbrella’. When giving and receiving feedback it helps to focus on what you like about the way your partner works - what we put our attention on grows and expands, after all. This was easy today as Igor is a sensitive, embodied and creative clown. We find we have a good foundation to build on - we read each room in the same way and have a similar sense of when to leave. We both feel supported - any ridiculous offer would be taken wholeheartedly by the other and built on, and a happy bonus - we find each other very funny. Igor reflected that I make clear offers, quickly. This was a compliment, but I know that it is something that plays against me too. Visits would also benefit from me allowing more time to let things emerge. An example from this morning was when a grandmother had specifically requested a visit for her grandchild who had been crying. I don’t think I had fully let go of an internal pressure to ‘fix the crying’ before I entered - a recipe for an offer that comes from the brain's intellect rather than the bodies. The girl was right at the end of the room, sitting on her mum’s lap. There were three older girls in beds around her. I brought out my tortoise puppet immediately, thinking this could be an indirect game that might end with the girl playing with it. Cuckoo faithfully jumped on board, and while he and the other girls in the room engaged happily, the small girl remained unsure. And the more unsure she was, the more invested the grandmother became. As it turned out, my indirect offer wasn’t indirect at all. In her desire to cheer up her grandchild, the grandmother signposted the game in neon, ‘THIS IS FOR YOU AND WE WANT YOU TO LIKE IT!’ We needed to retreat and try something else but I wasn’t sure what. At this moment I looked at Cuckoo as he brought out an orange scarf and simply threw it into the air. As it floated down, everyone's eyes lifted, their faces softened and their hands reached out for it instinctively. The purposelessness of the game and the softness of the image shifted the mood. The grandmother’s attention was on the scarf so the child relaxed. The scarf was gently passed around the room and the pressure released. Tomato was safely returned to my pocket without anyone noticing or caring and we floated out of a room full of smiling, relaxed faces. Without a robust reflective practice, I may have internalised this experience as a failure on my part, rather than being able to see the bigger picture - an example of good, supportive partnership in action. I am struck by how generosity, respect and responsiveness defined our morning and held us in a state of open playfulness and flow. Walking down through the park back into the city with Evgeniia after our shift, I am still a bit giddy. She describes a government initiative to make Lviv a more desirable tourist destination by cleaning up the city’s beautiful old doorways. She gestures to one with intricately carved handles and brass details bathed in sunlight and I wholeheartedly agree that Lviv should be a tourist hot spot. And then I catch her eye and she holds it for a moment and there is nothing more to say. I continue to experience a kind of emotional whiplash as we walk. We pass a vibrant book market. A huge statue celebrating Ivan Fedorov (father of Eastern Slavonic printing). Sandbags. A beautifully ornate church. A poster advertising ‘ShelterFest’. Sun dappled, cobbled streets. A dad in army fatigues. An absurd statue of a fish with hands coming out of it. My heart is beating between so many different sensations that I have no choice but to surrender. How do you feel? I don’t know, but I feel all of it, all the way to the edges. I’m aware that in an hour or so we will be delivering a 7 hour workshop to a group of Ukrainian healthcare clowns who have travelled across the country to be together and work with us. We arrive at an Armenian coffee house where, instead of the balanced and sensible lunch we had been planning on sustaining us through the afternoon, we drink rocket fuel prepared in hot sand by the most serious of baristas, and eat cake.

Our workshop is hosted at the Lviv Regional Academic Puppet Theatre - a huge and grand building in the middle of the old town. Marishka welcomes us and is exhausted after hosting a weekend of concerts there - the busiest she has ever organised. After drying our sweaty costumes on a bench in the hot sun, we settle into our room. Our first clown arrives, 20 years old, not-so-fresh off the train from Dnipro. She explains that the journey took 20 hours and that she is exhausted - the train has to go slowly in case of rocket fire. Not your average commute. The responsibility we have to hold this space with just the right balance of pastoral care, professional respect and playfulness drops into my chest. I connect to my centre, ground myself, make eye contact with Igor and breathe. The workshop we have planned is something that feels brand new for both of us and somehow simple and radical all at once. We will be taking a risk, but neither of us has the stomach not to try. These clowns' courage deserves to be met with courage; “Courage is the measure of our heartfelt participation with life, with another, with a community, a work; a future. To be courageous is not necessarily to go anywhere or do anything except to make conscious those things we already feel deeply and then to live through the unending vulnerabilities of those consequences.” David Whyte, Consolations: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words Here goes... Evgeniia Arakielian meets us at the door of Lviv Regional Children's Clinical Hospital along with Hristina Bogatirjova, one of the child psychologists based there. We can visit anywhere, except Acute Trauma. Fair enough.

Changing and warming-up alongside Igor today feels familiar already but the hospital itself is dramatically different from what I'm used to. I switch my focus to the work, which is identical - meeting the same needs (isolation, loss of control, trauma, anxiety, boredom) in the same way (presence, playfulness, connection, technique) to the same effect. The juxtaposition of being in an environment permeated with acute pain, anxiety and suffering whilst experiencing feelings of joy and exhilaration can be disconcerting; 'According to the UN children's fund Unicef, the hospital in the Ukrainian city of Lviv on the Polish border is overwhelmed by the number of injured children arriving from the contested regions...A UNICEF spokesman in Geneva reported that doctors in Lviv had to set up a sticker system to coordinate the treatment of the children. A green sticker means: injured but not urgently needed, yellow means: needs treatment, and red means: this child needs immediate attention. There are also black stickers, the spokesman said: the child is still alive, but it cannot be saved and the hospital is forced to focus its resources on other small patients.' . It is human nature to expect suffering and its recovery to be a serious business that requires our full adult, serious attention. Playfulness is a luxury reserved for when the Sun is shining, for when our hearts are full. Our luxury as healthcare clowns is that we can be the Sun. Our hearts can be full enough for everyone. Our joy and exhilaration comes from witnessing the various ways in which we see children, parents and staff expand into themselves throughout the course of the morning, as we ourselves expand to meet them. Our visits flow from room to room. A small boy on a bed giggling his head off at the fact that no matter how hard he tries, no matter how good his moonwalk, Cuckoo can’t enter the room without squeaking. In the end, the boys arm movements dictate the rhythm to a song and dance that free Cuckoo from his Squeak jail. Another boy with an arm recently put in a cast grows about a foot taller with pride at helping Maybee up from a bench she had been reclining on. A room full of girls giggling as Cuckoo tries to enter without Maybee seeing - first behind a nurse, then behind a pot plant. Another room with two teenage girls, a baby and a toddler who all help us play a lullaby for the pigeon sitting outside on the windowsill. The interactions with staff - hugs, smiles, compliments and warmth. Sunlight and love radiates, sticks to the walls, permeates the skin, reminds us all of our shared humanity, of what is still possible. At the end of our shift, Evgeniia says that she was reminded of the importance of play and humour as therapeutic tools, something that the serious task of being a child psychologist in a war zone over the last five months had taken from her. This afternoon we have our workshop with a group of Ukrainian healthcare clowns, who are travelling across the country to work with us. My memories of that first evening in Lviv are bathed in a golden glow. My dear friend and clown colleague Diane Thornton, who has extensive experience working in conflict zones as a theatre practitioner, had told me to expect the unexpected. And it’s true that I hadn’t expected to find Lviv so unspeakably beautiful. I catch myself looking for signs of war around me, on the faces of people passing by. The streets are busy - bustling even - but the atmosphere feels like the bit of a funeral wake where everyone has done their crying and now have to tidy up the old sandwiches and plates before they go back home. Sadness and resolve permeates everything, on a backdrop of stunning renaissance architecture and a vibrant cafe culture. We pass advertising boards that praise Ukrainian soldiers for their compassion and solidarity. The occasional government building is surrounded by sandbags and defences that I recognise from Saving Private Ryan. Occasionally we pass Ukrainian men wearing army fatigues who must be on leave from the front line. I hesitate to call them soldiers - they look just like my friends back home, wearing the wrong clothes. When we arrive at our hotel, there is a photocopied paper sign on the wall saying ‘Shelter’ with an arrow pointing to the basement. Nobody points this out to us, or explains the protocol. In fact we miss our first air raid siren, absorbed in writing and listening to music. Igor receives a message saying ‘are you afraid?’. He replies with a long message about finding Lviv beautiful and welcoming. ‘No, Igor - because of the siren’. ‘Oh’.

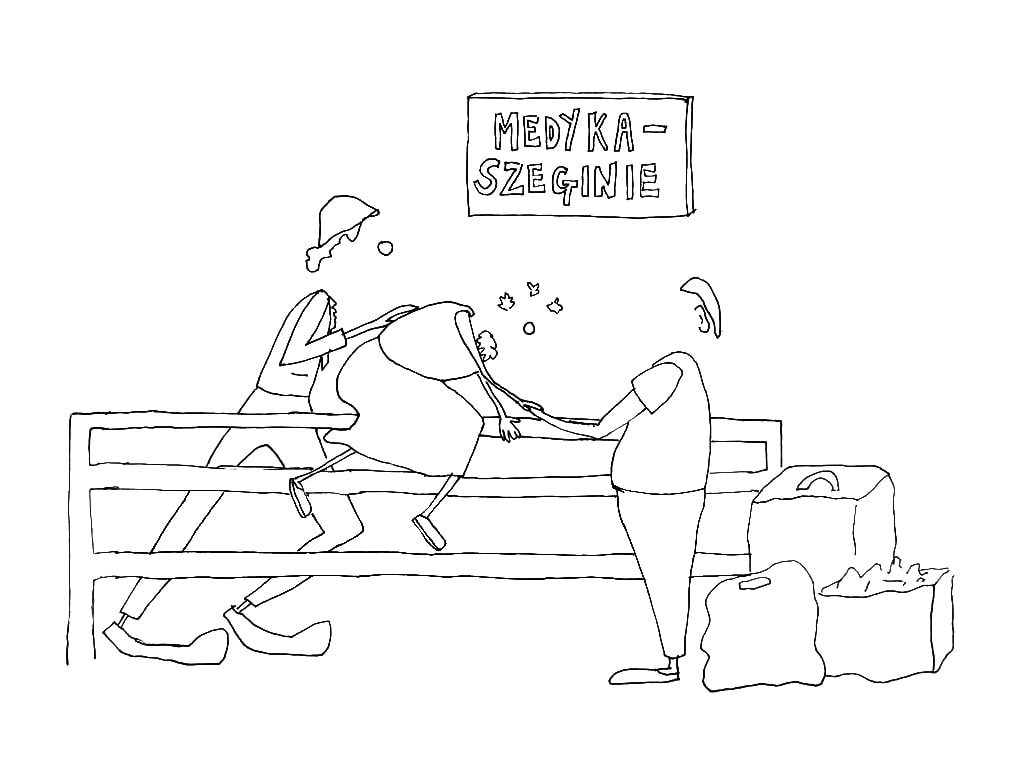

When we hear the next one - a sound at once totally familiar from films and intensely anxiety-inducing - we go downstairs. The ‘Shelter’ is the hotel basement. Next to the entrance there is a storage room filled with old paint cans and turpentine. There are no lights, no water, and no other people. I’d been following the news closely before we left, so I knew that the risk of Lviv being bombed were relatively slim. I’d also read that locals had long stopped responding to the sirens - in a choice between functioning on a daily basis and diving into a shelter because you believe you will die, this makes total sense. Cognitive dissonance reigns. In the morning when I ask the guy at reception if he ever goes to the shelter he laughs, ‘if a rocket hits us here we are dead - that shelter won't save you’. Gotcha. It’s 37 degrees and sweat is streaming down my face before I’ve even moved. We find a small patch of shade behind a tent to warm up - the gradual process of dropping down into my body, finding my voice, and finally connecting to this inner spark of joy, playfulness and love is delicious after so much time spent in transit. Any nerves that I had about being good enough are superseded by my strong desire to inhabit the refuge that is Dr Maybee, to do the thing I have come to do. It’s not busy on this side of the border. A food tent, UNICEF tent, information desks, a few volunteers line the path that leads to border control. Families - women and children - come in dribs and drabs, lugging too many, too heavy bags, eyes fixed on the border, hearts fixed on home. We agree that this time will be well spent finding a shared language so that we have something to build on the next day when we will be in hospital. Cuckoo and Maybee stand side by side and take a deep breath. As we inhale, Cuckoo’s leg lifts for our first step together. His legs are very long and he can lift them unfathomably high. Maybee stumbles. We look at one another: No matter! We must try again, and we must try harder! The second step works, a sigh and a smile of wonder and delight as we step forward into this new world together riding the wave of a pure and hopeful exhale. Within minutes, Maybee has her foot stuck in a huge black tarpaulin sheet and it seems there is no escape. The world of possibilities from just a few moments ago? Gone. She is destined to be here, in this tarpaulin, in the blazing sun, forever more. Cuckoo tries to sing her free with the harmonica to no avail, and then flies around looking for solutions - under the tarp, around it - all the while being directed by a man sitting in the shade who is laughing with delight. Finally the man shouts, ‘go down on one knee!’. Cuckoo goes down on one knee. ‘Music Maestro!’. Before we know it, the man is singing the wedding march in full voice, ‘Da da da daaaa, da da da daaaaaa’. Cuckoo takes Maybee’s hand and swings her into a dance, and she is released, spinning and twirling in amazement. Cuckoo and Maybee are married, love has set us free, and we have hit our stride. We both have a shared understanding in the importance of inhabiting a game and clown world that is rich and real and requires our full attention. People find Cuckoo and Maybee ‘in medias res’ and in this way our game serves as an invitation rather than a demand. Igor and I see people on the periphery and moderate our play to suit what we see, but we make don't insist. Passers by can feel safe to come close, to play on their terms or to walk on past. I found Ira Seidenstein’s description of this parallel reality very insightful; ‘Containing one's focus is the single most important discipline for an artist. They have to self-impose a form of ‘myopia’ or what I call one-sightedness. Yet, especially for a stage performer in acting and clown one must also have multi-sided awareness of the whole space and everyone in it. That Duality is: One-Sightedness, AND, Multi-Sided Awareness’ * We walk full of joy towards border control and as we near the door we stop with the sudden, sinking realisation - Cuckoo is on the wrong side of the railing. Our eyes meet. we look down at the railing, we look at one another, back to the railing, slowly back to one another....separated…forever…and so soon after the wedding! But no.. we must take courage…there must be a solution! As we quickly post Cuckoo through the middle of the fence, in her efforts, Maybee ends up balanced precariously on top of the railing. Cuckoo does his sweet, clumsy best to lower her down, but when a man arrives who is helping a family to cross the border and offers his hand, she takes it and is lifted, light as a feather, to the ground. Maybee is saved and her gratitude is boundless. Now Maybee and Cuckoo are bearing witness to an emotional goodbye between this man, two women and a small child. It seems the only thing to do is to hold this as gently as possible, to give their emotions space to flow. Maybee plays a melody on her ukulele and Cuckoo joins to sing the man's name. After a while, the women offer their names to be included, and the mood brightens as we celebrate this tender moment of deep gratitude. The girl, however, dramatically turns her back. She wants us to know that she is not okay about this. Just as we are saying goodbye, Cuckoo bends over and something squeaks. The girl is intrigued and moves closer with a smile. He gently touches her upper arm - squeak! She immediately giggles. She touches the same place and it squeaks again. More giggles. She does it again and again and again and the giggles have their own energy now, taking on a life of their own, as if she has started up a 2 stroke engine in her belly. Her mum touches her arm too. More squeaks, more giggles. They are all giggling as they pass through the turnstile and enter passport control, waving goodbye to their friend, squeaking all the way. Back out of costume we are queueing at passport control to cross into Ukraine. An old lady dressed in pink with bright, shining blue eyes comes through the door. She is clearly hot and tired, so I wave her ahead of me in the queue, without much thought. She tries to say something to me and I don’t understand. She tries again and I say, uselessly, ‘English…?’ and she shakes her head, smiling. She turns away to pick up her bag and then before I know it she is back, right in front of me. She takes my face in her hands, looks me in the eyes and kisses me warmly on the cheek.

It strikes me then that the more acute the pain, the more impactful even the simplest gestures of love can be. There couldn’t have been a more tender welcome into Ukraine. * I highly recommend subscribing to Ira’s newsletter: https://iraseid.com/international-school/newsletter Objectively, going to a war zone for the first time to clown with someone you met 3.5 months ago and have never worked with before might seem like a surprisingly bold risk.

On the plane to Warsaw, I woke up with a start. I had a nightmare that someone had sprayed a red swastika onto the baby of the people sitting next to me. As my stomach dropped to the cabin floor, the risk suddenly felt large and looming and my mind flooded with anxiety; ‘What are you doing? Is this vanity? Or ego? Can you really make any kind of difference by clowning? What if your clowning is so bad you make it worse for people? What if Igor realises that you don’t know what you are doing? What if you get bombed and everyone says ‘well she had it coming?!’ …I take a breath and remind myself: I have a rigorous, professional practice, and an interest in exploring the reach and difference that therapeutic clowning can make. In how we can respond to this rapidly changing and increasingly perilous world in an agile and meaningful way. To do that, you have to take a step towards the thing and look it right in the eye. You have to say yes. **** My clown partner on this trip is Igor Narovski, and we are here because we both do just that. Our journey through Poland is characterised by fantastically monosyllabic bus drivers. It seems to me that we are two little yeses being bounced between ‘No’s’ and shrugs and long queues. Two days of non-stop motion later - car, plane, taxi, train, bus, walk, bus, walk - we make it to Medyka, on the border with Ukraine where finally our clowns, Cuckoo and Maybee, meet... |

AuthorI am a therapeutic clown and performer. Writing here is part of my wider practice and maybe some of my thoughts will trigger some thoughts of your own and I hope that helps. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed