|

This is a sketch - a kind of field guide to connection, inspired by a recent visit to a Carehome where I accompanied a mother living with dementia and her daughter on a journey to a new kind of conversation, with support from Rights Made Real and My Home Life.

Imagine a path that is paved as the person you love walks it. And imagine that you are walking alongside them. With each step, you walk, not towards a destination, but into each moment. The path is paved by the act of you being present in this moment, together. Each encounter is new, each path unique and full of possibility. Gently let go of the ‘how are yous’ of everyday meeting, for this is not an everyday meeting. Allow yourself, instead, a moment to notice what is beautiful, and to share it...’oh! My love! Look at your shining blue eyes!’ As you walk slowly along, you see signs - invitations - for you to follow, like symbols on a map. Perhaps a gesture, a word, a breath, a glint in the eye, a touch. You notice them all and choose to follow one. First, you observe, carefully, without judgement. Now you repeat, feeling it in your own mouth or body, discovering your own pleasure in it. Next, emboldened, you begin to build and gradually explore - curious for where this tributary will take you both. Through this exploration, your loved one knows that they have been seen, been heard. You confirm their place on this path, and that you are there, walking in-step. They sense that what they have said or done means something important to you, and is worth repeating. Hitting your stride now, you make an invitation of your own - exploration becomes exchange as the path clears and the horizon comes into view, the sun-kissed landscape rolling out before you. You lift your eyes together, at all the possibilities, full of ease, grace and wonder. You will see, of course, that not all invitations are possible for you to travel together. Some will be a dead end for you or for your loved one, some will feel disorientating or confusing, some will simply disappear as you move towards them. There will be times when you feel lost or stuck. When you can’t see any signposts at all, when the fog comes down and the compass is spinning. It’s natural now to feel the loss. The despair of what is no longer there. The vertigo and fear that comes with constant change. The desire to to make sense of the senseless. That’s okay. When that happens, pause on the path-side awhile, sit on your suitcase and breathe. the breath is your North Star. When you breathe together, you’ll never be truly lost.

1 Comment

Today I feel like I’ve been plugged back into the mainframe. I’m so full of energy; I spent the day coaching/clowning with a DanskehospitalKlovne duo near Copenhagen and wanted to share this beautiful moment:

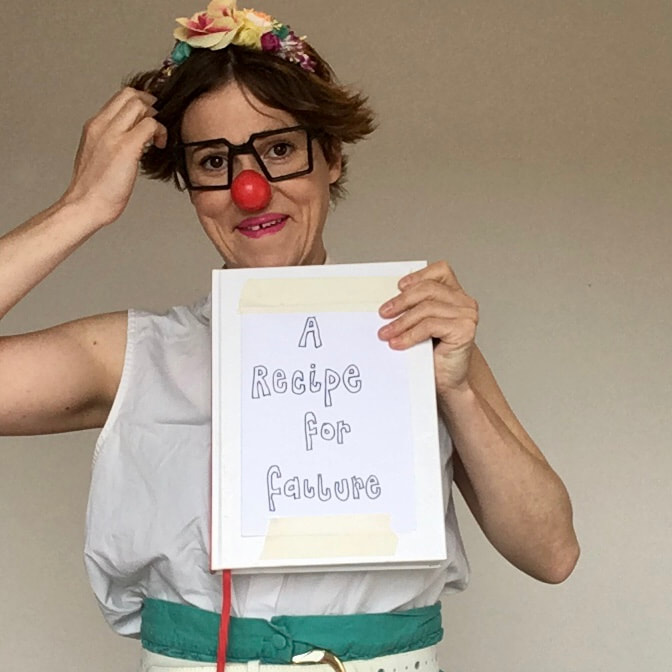

It’s the end of the shift and we are laughing as we bubble back down the corridor, enjoying the afterglow of the day, heads already drinking a coffee in the staff room. There are two residents on the corner, maybe in their 80s, frail. One sitting, one standing in front of him. Not speaking or looking at each other. Sort of hovering in one another’s orbit. As we pass, one says something like ‘can you play that thing?’ to Zippo, gesturing to his guitar. Zippo stops and begins to play. By now, I’m on the threshold of the staff room door but when I hear the music, I’m drawn back like elastic. I stand beside standing man and we are already feeling the groove, knees bouncing, hands dancing. Opposite, sitting man looks up and his eyes shine. I begin to play the trombone in the air. He nods and picks up his air trumpet. Now I am on the mic with the tall man, scatting, chhh chh chhaah chhhh chh chhhah dippiddy dappidy...When I look back, the sitting man is now on the clarinet. I give the saxophone a go. He laughs and the lights go down and we are in a smokey jazz bar, playing our usual slot. We are in synch, in flow, light as a feather, eyes bright. The cool cat crowd hang on our every note. They are in the palm of our hand. Sitting mans eyes flick to my skirt and back again. I look down...my petticoat is showing. Mortified, I quickly hide it and look back at him for reassurance. He laughs heartily and nods as if to say ‘it’s okay, kid, you got away with it’ and we play on until the small hours... It’s good to get the band back together. As part of the HCIM International meeting, I was asked to be on a panel about leadership, there to represent the 'next generation of Artistic Directors' that are taking over from our Founder/Ceo's. By the time of the conference (it was delayed by 1 year) I had handed in my resignation, I wanted to be honest about my experience on the panel and somehow only Dr Maybee knew how. People have been a little taken aback by my use of the word failure when talking about this. But I'm comfortable with the word...you don't do clown training without becoming comfortable with it. Failure is central to our work...and while of course it is a vulnerable place to be, it is inevitable & natural and a source of great learning and power. In refusing to feel shame, I hope that I can provoke a wider conversation and learning about how we structure our organisations and how we empower one another to thrive - just as we empower the people we visit as Therapeutic Clowns. So here it is, Dr Maybee's Recipe for Failure.  Ingredients: 1 x beloved organisation transitioning from Founder/CEO/AD in the midst of financial difficulty with no strategy. 1 x Skilled therapeutic clown with no interest in business and a lot of passion for delivering best practice. 1 x Board in transition whose longest standing member has been in role for 2 years.  Method: Set the timer for 4 years.  Step 1: Gather your equipment:

Overhaul training, communication & costumes with the artistic team. See a sustained and bubbling improvement in morale and the quality of delivery. Check-in regularly, stir occasionally and continue for approx 18 months. I knew that I needed this in order to stay grounded and connected to myself and the work, and found it so challenging to ask for it, even though the CEO at the time was very supportive. It’s hard enough to know what your needs are and express them. It’s even harder to insist on them when it seems other things are more important to your colleagues or the organisation.  Step 2: When the CEO leaves suddenly, pour over anxiety and marinade for 2 months. Add an Interim CEO who is deeply sceptical about therapeutic clowning and keen to make his CEO mark. Turn up the heat, go to the board and get him removed. Vigorously mix your courage and leadership skills and suggest to the Board that the AD and CEO should occupy the same shelf to address future power imbalances. Simmer gently when the Chair says no. I had this sense that 'this isn’t my world'. Everyone else knows better/is more confident/understands more/is more experienced, so I didn’t voice my misgivings at first. I didn't feel I had the personal or positional power to express my concern. Of course, this is my 'stuff', but it also comes from the Patriarchal structures and systems that surround us, that have surrounded me since early childhood, that show leadership as a white middle aged man in a suit. The organisation relied on good chemistry and communication between the CEO and AD but there were no systems in place to support that or to support us if things went wrong. The final say would always be with the CEO as the top of the organisation which meant the AD would always be vulnerable to an imbalance of power. The combination of that, and my feelings of responsibility to the programme and the artistic team soon became totally unmanageable.  Step 3: Now quickly discard the parts of the AD job that you love to become Interim CEO for approx. 4 months. Stop practice, studio time and stretching during meetings. This is now ‘unprofessional’. Meanwhile, scatter more spreadsheets, budgets, meetings and stress onto your agenda. Cut programmes in half, lengthways. Stop sleeping. Keep an eye on the artistic team and continue to support them to flourish, build trust, and deepen their practice, despite the shrinking artistic programme. People seem to find it amusing when I say how difficult I find it to work with budgets or spreadsheets, as if it is a question of simply trying harder or applying myself. I never question anyone when they tell me they would be terrified to perform in front of a crowd of people, and it would be absurd to expect someone to do that without all the support they needed in order to thrive. Boards and organisations need to really take a look at how to make their organisations inclusive and accessible in a meaningful way to people who embody different ways of being in, seeing and experiencing the world. How can they encourage, welcome and make space for people as their whole selves? The people who love spreadsheets and details and the ones who are terrified of them?  Step 4: When you notice the pan smoking, recruit a bright and brilliant new CEO and set aside your worries. Sigh a sigh of relief for around 1 minute.  Step 5: Make a suggestion to put ‘Pandemic’ in the risk register and laugh along as everyone else laughs at you. When the pandemic comes to the boil, your chefs instinct will tell you to pause and reflect. Many people in the team have caring responsibilities. The CEO will continue to stir with enthusiasm and vigour. Hold onto your mental health - you might need this later. Divide your time between creating a new digital programme, teaching yourself video editing software & skills, creating online content, supporting the artistic team and managing your anxiety. At this point it’s normal to feel both proud and overwhelmed.  Step 6: Add renewed conversations about Strategy, the need to innovate and diversify and notice that the hierarchy of the organisation and of information feels more pronounced. Stir in a feeling of unease and clarify your artistic vision. When conversations reach boiling point, suggest the SMT gets team Supervision. First, learn that not everyone is as comfortable with emotion as you are. Then, gradually learn that the rest of the SMT thinks you are inflexible and they don’t support your artistic vision. There are no more sessions. Discard. Sprinkle over some paranoia and Prozac. Mix in the feeling that the CEO would like creative control. It was always my instinct and way of working to be open and transparent with the artistic team. Many of them are more experienced than I am and run their own theatre companies. As time went on, there was more language in the SMT around not telling the team about certain decisions as it might worry them - a leadership style that was at odds with my own.  Step 7: To make sure your failure is certain, recruit a dynamic new General Manager who who uses the word ‘unprofessional’ when talking about the artistic team, highlights your many administrative errors, and suggests ‘breaking the mould’ of best practice. Attempt to be open and honest about how impossible and undermining the situation feels. Stir in powerlessness. Now mix in the feeling that your role is redundant. Repeat this process for a few months. Sandwich yourself between the SMT and the Artistic team and spread yourself thinly. Now is a good time to check what the alternative artistic vision for the organisation is. If the CEO says ‘I don't know, I just know that we have to be open and flexible’ one more time, you know your failure is nearly ready to serve. I want to emphasise that the team were good, skilled people. Everyone was doing their best. But of course people are very messy. We bring with us lots of internalised bias, preferences, needs, likes, dislikes and insecurities. In many working environments, being ‘professional’ means not showing any of these things. As a matter of fact, what is deemed as ‘professional’ can be extremely narrow and uninspiring. I understood at this point that this wasn’t a dip, but that I had reached the end of the road. Leaving felt like the only act of agency available to me. I had to trust that I would find other ways and means of serving Therapeutic Clowning and at this moment, my mental health had to come first.  Finally, share your letter of resignation with the artistic team as an act of defiance, transparency and hope. People say they love having an artist in the office but not, it seems, if that means compromising their preferred ways of working and being. There is very little space or understanding of neuro-divergence, or divergence of any kind in many workplaces...and according to this article I read last week: 'Roughly one in 20 people have ADHD. We know that one in 10 have dyslexia, one in 60 have autism – and in fact roughly one-fifth of the human population are neurodiverse. One in five people can’t be seen as errors of genetics. We have to acknowledge there is diversity of human neurocognitive capacity and we’re all the richer for it.' (read the article here)  Enjoy your failure with friends! Great with a side salad of perspective, humour and learning. It is ableist to frame neuro-divergent people’s worldview, behaviours or ways of interacting as less desirable. This 'failure' in my role as AD has helped me to realise how much effort and energy it took me to fit into society's neurotypical expectations of me - throughout my life and most acutely in these last 4 years.

It has been a very cathartic and healing process to write this and to share it. And I do it in the hope that our organisations take a pause, and really, really listen. I know I am not the only Artistic Director who has struggled, and I know that there are General Managers and CEOs who are also challenged by this working dynamic. I don't have answers, but I feel certain that listening and being present is a good place to start... And in the meantime I am good. I chose freedom, and all is well. I suppose I arrived at the HCIM meeting wondering if I had any real place there anymore since leaving Hearts & Minds.

On the first day as I walked into the conference, I braced myself. I edited my response each time I was asked ‘what happened?’ - reframing, attempting to apply logic and wisdom and insight when really all I felt was heartbreak. After I heard Laura Van Dolron, our stand-up philosopher speak, I went to the bathroom and cried - big, fat, hot tears that just kept coming. And then I emerged into a warm hug, and laughter, and sweetness and later some very excellent dancing. Over the next 2 days, I felt validated, and held and connected. I was so touched by people taking me aside to remind me of why I am here, and what I have to offer. And I was able to contribute - my first experience moderating a panel, and I loved every second of it. When I got home I opened bell hooks: All about love (2000) and read this passage: “Communities sustain life - not nuclear families or the couple, and certainly not the rugged individualist. There is no better place to learn the art of loving than in community…M.Scott Peck defines community as the coming together of a group of individuals ‘who have learned how to communicate honestly with each other, whose relationships go deeper than their masks of composure, who have developed some significant commitment to ‘rejoice together, mourn together’ and to ‘delight in each other, and make other’s conditions our own’” And I thought YES! Yes, this is us. And this is my community. Once again, the clown has healed me and I am overflowing with gratitude, and I'm writing again. (Written while in post as AD with Hearts & Minds)

Brain Awareness Week got me thinking. Thinking about how unhelpful thinking is when you are clowning. Thinking about how thinking about not thinking is even less helpful. Thinking about brains and bodies. In face of the prediction that 131.5 million of us in the world will be living with dementia by 2050 and that according to EPAD (European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Dementia Consortium) there hasn’t been a new medication for Alzheimer’s in the last twenty years, it strikes me how important it is that we pay attention to how to be with and celebrate a person once their brain doesn’t work as it once did. To consider that we are more than our brains. We are bodies, and as Jules Montague puts it in her ted talk, ‘embodiment allows people to exist in the world, to be resolutely present...it is our gestures, habits and actions and Dementia can’t take that away.’ As therapeutic clowns we are responding with our whole body and not just our head and thinking brain. The thinking clown might come in to a ward with a plan to entertain, but the embodied clown will arrive with the intention to meet someone in their gestures, habits and actions to create a tailor-made theatrical experience. For it is in this embodied place that we share and recognise our humanity and sense of self, regardless of cognitive capacity. By using therapeutic clowning to connect in an emotional, person-centered way, we observe that people become more verbal, more interactive and less isolated – observations backed-up by recent compelling research by Daisy Fancourt that the arts can play a vital and central role in the general wellbeing and cognitive health of people living with dementia, ‘enjoyable activities can induce positive affect and heighten arousal which has been shown to lead to improved cognitive performance.’ Intellectual thinking is highly prized to humans, but profound experiences of human connection rarely have anything to do with rational thought. (Written while in post as AD for Hearts & Minds)

When people ask what I do for a living, once we’ve established that it is not frightening children, they often comment on how difficult and sad it must be. It’s hard for me to see this job as sad. My overwhelming feeling is that it is rewarding and exciting. I regularly see the transformation of a child lying down in bed with tubes coming out of their arms, pale, unengaged and anxious to a child sitting up in bed laughing and controlling the action. On dementia wards it is the same. People seemingly locked in their own worlds unfurl and begin dancing and singing with us. It is a huge privilege and often joyful. Of course the reality is that we are often visiting very unwell people and there is potential for this to affect us personally. There are days when we come onto the ward for our handover to hear that someone we regularly visit has died and this is upsetting. But the clown doesn’t just help us to connect – it also keeps us emotionally safe. Once we are in our clown state, the present moment is all there is. And for a clown, the present moment is always full of potential for shared joy and playfulness. Self-reflection and collaboration are built into our practice. We work in pairs so that we can check-in with one another – take a moment to refresh, breath, reconnect if needs be. Regular confidential supervision as a team gives us space to celebrate and grieve in a natural way. We know that burn-out is a possibility and we look for red flags: when we start to feel indispensable, ‘but it has to be me who goes to that unit’ and a sense of ownership, ‘I’m the only one who can connect with that person’ and then we do something about it. It isn’t always easy, but it is our responsibility to ensure that we are in a fit state to do the job that we are required to do. Ultimately, we know that their struggle is not our struggle. Any difficulty we encounter is not ours to bear and for this reason we can invite people out of their circumstance to meet us in worlds of play and imagination. (Written while in post as AD for Hearts & Minds)

“Making fun is serious business. It calls for deep study, for concentrated observation” Charlie Chaplin We take the artistic quality of our interactions as Clowndoctors and Elderflowers extremely seriously. In a healthcare or school environment we have no contract with our audience. No-one buys a ticket. No-one books to come to us. There are no reviews from theatre critics. We enter the space, often at a time when people are in a time of crisis, anxiety or pain. The stakes are high and the possibility of us making the situation worse rather than better is real. To make certain that our visits have a consistently positive impact requires artistic rigor, professionalism and continual high-quality training. And the training for this work is as rich and nuanced as the work itself. We need to attend to ourselves as actors and our ability to work with control, clarity and intelligence. We need to attend to ourselves as clowns and our ability to be truly alive to the moment, able to believe with our whole hearts in the importance of the task at hand. Our improvisation skills need to be constantly honed. We need to work on our technical skill – singing, mime, puppetry, musical instruments – so that we can bring our imaginations to life and transform experiences for the better. We need to understand how to work non-verbally and with all our senses. We need to build trust as an ensemble and in partnerships. We need to understand the complexity of environments in which we work in order to work effectively alongside healthcare professionals and teaching staff. Thanks to support from Creative Scotland this year, our bi-monthly team training days have been supplemented by three separate weekends led by outside trainers. Sophie Gazel, Ira Seidenstein and Cai Tomos will between them give us fresh tools, techniques and ways to understand our practice, our artform and our impact. These expert perspectives help us to see ourselves and the work more clearly. To pinpoint where we need to work and how we might do so. I understood when I first put on a red nose in 2006 that to call myself clown was to commit myself to a lifetime of learning. That is even more true when that clowning is in the service of others. (Written while in post as AD for Hearts & Minds)

How to capture the impact of our interactions more effectively has been a question on my mind for a while. Until a recent meeting with Evaluation Support Scotland, I had the feeling that proof and evidence of our value had to be crunched into numbers, graphs and pie charts to be credible. It felt demoralising. As practitioners we recognise when a child is experiencing being more in control, being immersed in play, feeling happy. As a society we understand the value of these things to our wellbeing, and we understand the importance of wellbeing. Here are a few stories from my day at a school last week: My Clowndoctor name is Dr Maybee, and on this particular day I was working alongside Dr Spritely. These visits describe the kinds of interactions that we regularly have in an SEN school setting. First we met Alfie* who has a room of his own with padding all across the walls and floor. He is strong and he is constantly on the move. This was our second meeting with him. After spending 5 minutes with him, listening & waiting, Dr Maybee took out a sound tube and blew through it like a trumpet. He looked immediately and put the other end to his ear. She made the noise again and he grinned. She built to a beat box rhythm, and every time she did a high-pitched noise through it, he looked at Spritely (equally delighted) and they laughed together with pure joy, looking into each other’s eyes. He stood with us, laughing joyfully, controlling where the sound and vibrations were on his face for a full 5 minutes. Next we visited Matthew* who spends the day moving from place to place banging his hands against different surfaces as hard as he can. After a few minutes of being in the room with him and mirroring some of his movements he sat down. Dr Maybee sat next to him. He started chewing on the straw of his water bottle. Dr Maybee looked on, very jealous and wanting some. She said, ‘Oh wow, that looks soooooo delicious’. He passed the bottle to her and she pretended to drink from it, making huge slurping noises. He giggled. She passed it back to him and he chewed on it again. Then Dr Spritely asked for some – upset that she had been left out. He gave it to her. More slurps. More giggles. This sequence repeated a few times before he stood up and began his loop of banging on surfaces again. Afterwards, his key worker said that she had never seen him share anything before. For our final visit, Calum* in P1 started the visit sitting on his key worker’s lap and would look away if we got any closer than around 3 meters. Dr Maybee began playing some music and wanted Dr Spritely to stand in the right spot. Spritely kept moving. When Maybee told her off, she got very upset and had a tantrum. The boy giggled, so each time, the tantrum got bigger and more physical. Then the boy started to encourage Spritely to move to the wrong spot and as he did this, Spritely got closer and closer to him until they were nose to nose. He was giggling in delight the whole time. I see now that our work isn’t to just speak the language of science in our evaluation but to be confident in communicating the human impact of what we do. As Vassilka Shishkova says in her ETM Toolkit, “The last thing you would want from a public transport service is to surprise you, to bring you to new places or to make you ask questions. Since this seems obvious, why do we still try to evaluate our art the same way?” (Written while in post as AD for Hearts & Minds)

This month I read two articles that got me thinking about clown’s relationship to failure. The first article was one on the BMA website (April 2019) stating that the NHS is facing a serious mental health crisis amongst doctors and medical students, with fear of failure sighted as one of the main reasons, “many doctors and medical students can often feel a deep aversion to ‘failing’ and perhaps can’t even perceive what failure would really mean or look like.” (Prof. Dinesh Bhugra CBE). The second was ‘Seriously Foolish and Foolishly Serious: The Art and Practice of Clowning in Children’s Rehabilitation’ (Julia Gray & Helen Donnelly & Barbara E. Gibson: July 2019) – a reclamation of foolishness as important in and of itself in the context of children’s rehabilitation in an environment that favours ‘certain high forms of knowledge…over lower embodied, imaginative and active knowledge forms’. I think about the clown’s relationship to failure a lot. Learning to confront and embrace one’s failure is central to any clown training programme and while doing so can be frightening and exhausting, ‘Through clown training, theatre artists aim to be less defensive, exposing naïveté and fragility’ (Gray; Donnelly; Gibson: July 2019) it ultimately gives us freedom to “fail hopelessly, imaginatively, unluckily, triumphantly, heartbreakingly and barely… shrugging off social expectation to shoulder the weight of the world playfully” (Failure as success: On clowns and laughing bodies. Eric Weitz: Feb 2012). This is evidenced beautifully in vintage clips of Lucille Ball, Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin. The clown’s embrace of failure is one way they elicit laughter, but the function of failure goes well beyond humour, especially in a healthcare setting. It allows the people we visit to feel superior and ‘successful’ in a highly hierarchical environment where success might otherwise be perceived as equal to recovery and good health. It allows us to be with people as they are in the here and now, in their pain, sadness, and discomfort. As Donnelly et al argue, as therapeutic clowns, we do not focus on ‘fixing’ the child or solving the problem of their circumstance, rather, find ‘fluid ways of being playful, sensory, emotional, vulnerable and in-relation‘. As the BMA article demonstrates, fear of failure is isolating and at its worst, catastrophic. When we accept that failure is natural, universal and inevitable, we can find ways to be in the world and with one another that are more connected and humane. APRIL 2020 (Written for Hearts & Minds)

Adaptation: The process by which a species becomes fitted to its environment. ‘Connecting to our vitality, to play, to our imaginations and creativity is a vital means of survival.’ Esther Perel Here are 5 things that we have noticed so far when adapting our therapeutic clown programme to an online environment: 1:2D v 3D When we are in the same space, we notice the tension in the body, whether toes are tapping, subtle invitations for play or for pause. What used to be 360 degree fully sensory experiences are now a flat image on a flat screen and often only a face. ‘Reading’ the young people and ladies and gentlemen that we are visiting is different. On screen, we are learning to take our time even more, to trust ourselves, our instincts and the person on the other side of the screen. 2: Physical space We are used to inhabiting the same world as each other, transforming spaces together and creating opportunities for laughter and play in the same physical space. Now, no longer in the same world, we create that illusion together. Bumble bees have passed through cameras, balloons launched from the child’s world into ours, noses squeeked through screens. Perhaps we are beginning to subvert TV Land in the same way that we subvert hospital settings? 3: Eye contact Eye contact has always felt like an important part of this work, ‘an actual meeting of actual eyes transmitted through the air of a shared room’. But on camera the kind of real eye contact that we are used to is not possible. In working with this challenge, we are reminded that this is not fundamental to connection. Many of the young people we visit are visually impaired; have complex learning needs; advanced dementia. We know that we can connect without eye contact. We can still ‘see’ one another without looking into each other’s eyes. 4: Thresholds After a day of visits we sit together with our partner and talk about the day. We change out of costume, leave the hospital, catch a bus, write our notes. When an online visit ends, we are in our own home suddenly. We land with a crash into reality. It is more important than ever to create a ritual, and ending, a boundary between the virtual world we were just in and the daily lockdown life we are returning to. 5: Meaningful connections Meaningful and playful connections are still possible and as real as ever. We see it in the responses to visits that young people and their families are actively engaged in imaginative play with us, laughing and controlling the action in the same way that they do when we are in the same space. Ladies and gentlemen living with dementia are laughing, sitting up in their seats and participating during our visits with them. We are able to bring vibrance, joy and laughter to people in times of profound uncertainty and distress. This is a relief. We will continue to embrace doubt, mistakes and uncertainty as tools that teach us to do better, to adapt and to grow into this new world joyfully and wholeheartedly. |

AuthorI am a therapeutic clown and performer. Writing here is part of my wider practice and maybe some of my thoughts will trigger some thoughts of your own and I hope that helps. Archives

March 2023

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed